Today Ronan and I cuddled on the couch in the early morning. He read his new book and flipped through his art cards (black and white sketches of a panda, a ring-tailed lemur, an anteater, a penguin) while I composed a long-overdue list of thank you notes owed for his many birthday gifts. His spasticity is worsening (his hands spring together when he’s on his back as if he’s holding magnets in his palms), and when I think about the effort it takes for him to reach out and turn the pages of a soft book I want to squeeze him and never let him go. But I let him grunt and reach because it’s what he wants to do. Even a dying baby can have ambitions of a kind, and I’ll allow him his.

Today, like every day, I wish I could heal my son. As he becomes more withdrawn and sleepy-looking (“It’s like he’s moving underwater,” Rick observes) I would give anything, do anything, to make him better, to make him well. But what would that healing look like? Might it already be taking place in some way beyond the powers of imagination and simple belief? What does it mean to “be well?” Who decides what healing is? What does it mean to be whole?

Today I’m thinking about Michael W. Smith, a singer-songwriter popular among the evangelical Christian group to which, in junior high, I briefly belonged. Take pity on me. I had just moved to a small town in Nebraska where all the girls had grown up together. I was friendless and nerdy, and easily roped into weekly prayer meetings and daily journal entries about “how Jesus works every day in my life.” Unfortunately, my entries, made faithfully, were not well received. Our leader was a bespectacled, balding man in his early thirties, Mr. S., who preached to his captive audience of fourteen-year-old girls teetering on the edge of puberty about why it was important to abstain from sex “until one is married,” and why The Simpsons was an evil television show to be avoided no matter what, “even if it makes one look uncool.” In one of our “private growth meetings,” a description that still makes no sense to me (what were we expected to grow out of or into?), which consisted of Mr. S asking me questions about my faith (“Do you notice our Lord and Savior moving in your heart each day and do you thank him?”) and me responding with what I thought were the appropriate answers (“Yes, and yes”), he flipped through my journal and sighed. “They’re not supposed to be stories, Emily. They’re supposed to be prayers. There’s a difference.” Oh.

I was no good at prayer, it seemed, in written form or otherwise. The prayer circles, when we girls stood huddled together, swinging our arms and saying Jesus, I just hope that you’ll just heal us and just please please please make us whole and free us from sin and Jesus, please just take pity on us, we sinners, for all of our trespasses put me on the edge of giggles and I could not keep my eyes closed as instructed by our “leader,” a droopy-faced girl with bleached hair and a pair of shoes to match each of her brightly colored outfits. I felt vaguely embarrassed by these emotional outpourings. Couldn’t we just sit down and pray quietly like Lutherans? But no, these upstart Christians were not the demure churchgoers of my early childhood, they were evangelicals, a new word to me, and I wanted friends, no matter how they referred to themselves. So I wrote in the journal and I swung my arms and asked to be saved and earnestly scrunched up my face with the others. During this period I also attended Christian rock concerts, even though the melodies were horrendous and the lyrics even worse.

Michael W. sang a song about a girl called Emily who had died – perhaps of cancer or in a tragic accident, I can’t remember – but in any case, Emily was dead, and Mr. Smith had written a schmaltzy, cloying song in her memory. You’re an angel waiting for wings (meaningful pause) Em-il-y. During the song the girl sitting next to me (Ashley? Katie?) turned to me and said, “This song is about you, Emily.” Her eyes were shining. “Uh, that’s my name,” I said, shifting in my bleacher seat. She put her hand on my knee. Her white beaded “promise bracelet” that indicated her commitment to wait until marriage to have sex dug into my thigh. “Someday you’ll go to heaven and be healed, and then you won’t be crippled anymore.” I imagined myself as a celestial super model, all arms and heavily mascara-ed eyes and flowing hair, strutting down some heavenly, cloud-strewn catwalk. And then I really did laugh, so hard that it looked like I was crying, and she put her arm around me and we rocked from side to side. “I know, I know,” she cooed, and we swayed together for the rest of the song as she softly muttered, “Heal us Jesus, help us Jesus, save us Savior please.”

Years later, I’m still stumped. Did being healed mean being made to look “normal,” in the sense that I’d have my leg back and look a particular way? I found and still find the image of myself equipped with two “real” legs, running around in heaven doing who knows what, patently ridiculous. Wasn’t heaven about transcendence? Wasn’t the physical body rendered useless or unnecessary as it was just a vessel for the soul inside, the thing that needed saving? This is how I’d interpreted the Biblical passage where Jesus appears at the mouth of the empty tomb and instructs his grieving visitors not to worry. He was fine! His soul was up in Heaven with the Father and he was beyond all bodily concerns, the horrors of the crucifixion already a dim memory. I imagined myself as a kind of holy phantom rushing around like wind in the clouds, my soul united with all the other souls that had gone to the right place, all of us bodiless and free. This is how I’d pictured heaven as a child, and now I felt confused, or at the very least like talking about it. I asked our youth director about this issue at one of our “growth” meetings. He blinked at me. “Heaven is the resurrection,” he stated firmly. “With or without the body?” I asked. (I could have debated this issue with my pastor father, but I was a teenager and therefore convinced that he knew absolutely nothing about anything.) “It’s a resurrection,” he repeated. “It means you’ll be perfect.” “You mean normal?” He blushed. “Yes that’s right,” he said finally. He handed my journal back to me. “You’ll be perfectly normal. Isn’t that something to look forward to?” Resurrection=Perfection? Sure.

Flash forward sixteen years. I’m a writer-in-residence at a college in rural Pennsylvania. On this particular autumn afternoon I’m sitting in a living room with a group of divorcees ranging in age from 30 to 65, learning to practice the healing art of Reiki, Level 1. Reiki is a system of energy healing that involves the laying on of hands at certain points (face, chest, shoulders, etc.) on the patient’s body. The practitioner’s palms channel healing energy to the patient that, far from being prescriptive, has no predetermined end point but is meant simply to serve that person’s “highest good.” Several months before I’d seen an ad for a Reiki healer in the local grocery store, figured I could use some healing, and became instantly addicted. After weekly treatments I left my practitioner’s small house perched at the end of a gravel road feeling electric, euphoric, and weirdly complete. “I can feel your whole left leg,” my practitioner said. “It gives off its own energy, even though it’s not there.” “Like phantom limb?” I asked. She nodded. “Only without the pain attached.” No wonder I felt so fantastic.

During our first training session the Reiki master, a tall blond woman from upstate New York, was educating us about the Reiki notion of wholeness. “See this,” she said, pointing to the image of a torn leaf. Where the other half of the leaf had broken off she carefully drew a dotted line. “In Reiki, everything is whole, or at least holds the whole within itself. In other words, all of you are already perfect.” A few women started to cry.

I raised my hand. “So healing could mean something unexpected. I mean, it wouldn’t necessarily look the way we think it should.” A small water fountain trickled in the corner of the room. Red and gold leaves fell past the window outside. I tried to imagine myself as an uncrippled angel, spiriting through the lawn.

The master nodded. “The idea isn’t about achieving wholeness, but about what the body of that person needs, and this wisdom is housed exclusively within the body itself.”

“What about curing things, like ailments or pain, or what about cancer?” one woman asked.

Our master motioned one of the students over to the table and asked her to lie down. “Reiki energy doesn’t help save people in the way we’ve come to understand it according to Western medical practices,” our teacher cautioned. “It simply helps the body do what it needs to do.” In the case of her father-in-law who had stage 4 cancer, the healing energy allowed him to die peacefully in his home. “I treated him every day,” she said, “until the very end. Dying was what his body needed to do.”

“So it helps with hospice care?” one woman asked, her voice trembling. She had just been left by her husband of thirty years for a twenty-something graduate student and now her mother was dying. She was learning Reiki to try and help ease her mother’s passage when all conventional methods of comfort had failed. The master hovered over the woman on the table, inhaled, and placed her palms on her shoulders. “That’s exactly right,” she said. The woman who had asked the question nodded and burst into tears.

The Reiki method of healing trusts the body to give itself what it needs with the practitioner’s help and the healing is directed to moment-by-moment experience, not to an end goal. (There’s an instructive parallel here in terms of writing, which has the cathartic power of a therapeutic practice but lacks the ultimate goal of traditional therapy: wellness, regulation). As I drove home from those Reiki treatments down the rain-soaked rural Pennsylvania roads, I felt calm, complete, and content. Vibrant and settled. A kind of healing, then, but not one that involved a dramatic physical transformation or a sudden adoption of a new body. A new leg did not miraculously sprout forth to help me start running heavenly marathons. It was much more complicated and pure than that.

Still, I was skeptical. Healing to me meant, in some weird way, exactly what that girl had described to me at the Michael W. concert. “Fixing” someone – their life, their body – meant aligning their experience with a preconceived notion of what made a right, good life: marriage, kids, beauty, bodily perfection, which in turn meant health and all limbs intact. It sounds so simplistic, and it is, but it was the worldview I’d been taught to believe in and it stuck.

When I treated the woman whose mother was dying, I felt the change in energy as I worked on different parts of her body. There was coolness at the forehead and on the shoulders and an unmistakable heat all around her heart. After the treatment she seemed relieved, and when she treated me I also felt a great lift, a shift into a surprising but gentle equilibrium. Nothing was “fixed.” That woman’s mother was still going to die painfully, and it would take me years to recover from an abusive marriage, but something was happening. The air was different. The room felt charged. Could these shifts be proven diagnostically, under a microscope or in a therapy session? No. But was healing taking place? I think so.

What does this mean for Ronan? I give my son daily Reiki treatments and massages. He sees his acupuncturist each week, and a physical therapist comes to our house twice a month.

And last month he saw a Japanese Sensei. This renowned teacher of acupuncture treated both of us in a large, sunlit room that reminded me of a church fellowship hall, but without the smell of percolating coffee and without a single donut in sight. Lying on tables organized in careful rows were people in various stages of partial undress. Above them, hovering, touching, laboring, were three or more acupuncturists taking pulses, touching feet, inserting needles and quietly consulting about the diagnosis in urgent whispers.

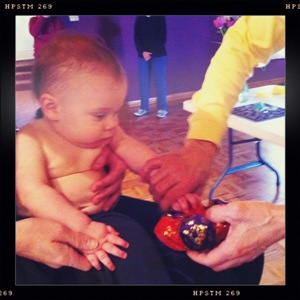

A crowd of people gathered around Ronan. He squawked, loving the attention (he inherited more than just the Tay-Sachs gene from me). Tiny tools that resembled metal toothpicks were used to stimulate points in his chubby knees and along his stomach and back. Ronan played with a colorful blue and gold pillow as Sensei scraped his meridians and diagnosed him: a weak spleen. But, he said, “he tells me he’s happy.” Ronan squealed happily. When it came time for my treatment, three different pairs of hands massaged and needled and diagnosed. “She’s strong but fragile,” I heard someone say. “Here, work on this meridian.” When there was a change sensed in the body, the diagnosis changed, the strategy changed. Each moment was taken individually. The end goal? To enable the body to do what it needed to do, whatever that might be, in that particular moment. In other words, no breaking free of the leg braces a la Forrest Gump, no miraculous healing of a disease that somehow suggests an open landscape free of pain, a future that is fixed and pain free or without struggle.

In both Reiki and acupuncture, there is no effort to make anyone “whole” or “better” in the way my friend at the Christian rock concert had understood it. My youth pastor led me to believe that my real life, my perfect life, would begin after my death, and that what I did on earth was merely a preparatory journey for that final transformation. (I think about the call and respond during Easter Sunday services: “He is risen!” “He is risen indeed!”) For Reiki masters and acupuncturists of many different lineages, the goal is comfort in the moment, now, here, in your body. The second approach, especially in light of my experience of parenting Ronan, makes a lot more sense.

Near Santa Fe there’s a village called Chimayo, famous for its “sanctuario” of healing dirt and for the annual Easter pilgrimage when long lines of faithful penitents armed with electric torches and illuminated clothing traipse to the church along I-25. I’ve been to Chimayo at least five times since moving to Santa Fe, the last time this winter. In a quiet back room of the main church, a small hole in the ground is full of soft, dark dirt that is cool to the touch, like slightly damp sand. A handwritten sign on the wall tells you that if you have a handicap (check) and a broken heart (check) you will find solace here. I don’t believe this, not really, but I always find myself scooping up a bit of the dirt and rubbing it on myself and on Ronan. I like the mystery inherent in magical thinking, the glittering possibility. And what do we really know? Very little, it seems. And I do find solace here, strangely, if only because those who visit Chimayo for healing seem fueled by ardent, inconvenient beliefs, and this struggle suggests a powerful stubbornness that I can appreciate.

The walls of the corridor outside the room are lined with shiny metal crutches, a few raggedly looking canes; all apparently abandoned after the healing dirt did its magic. The entirety of one wall is papered with photographs of service men and women who have died in the last ten years in various wars, the bulk of them between 19 and 23 years old. The place is bustling with people during the summer months, but during the winter there are no pilgrims, no hustle of bodies or rosaries being slipped through the fingers of tourists at the Vigil Store. On this last visit it seemed that nobody was keeping vigil at all. The churches were bone-cold, the pews empty. There was a man sawing a piece of wood in one of the side chapels where an elaborately dressed doll, wearing blue and white fluttery skirts – the Madonna — stood collecting dust behind a pane of recently cleaned glass. A creaky wooden sign advertising espresso drinks in a side street café creaked back and forth in the wind. In the children’s chapel, the back room was stacked wall to wall with baby shoes for Santo Nino, the walking baby saint, and a woman was singing “the Old Rugged Cross” as she swept the wooden floors. I love the religious folk art, the red and blue wooden birds swinging from the ceilings, the sky blue birds perched at the baptismal font and the random stray dogs that will wander in and lick a baby’s hand if you sit in the pews long enough. Just outside the door are a few children’s graves that I’d never noticed before. The entrance gate is guarded by a colorful symbol of Santo Nino himself, all cherubic golden curls and red and yellow robes. I go to Chimayo because I don’t believe in any of what’s offered there, but I want to: healing as a magic trick, physical salvation at the flick of a sanctified wrist, dirt placed on the affected parts that leads to a stunning change. I want someone to say, as Jesus did to a man’s dead daughter in the gospels, “Child! Get up!” But I know it will not happen. But something else might.

In central California I once saw a scrappy front yard that was heaving with

statues of saints, Anthony and Jude and others falling all over one another to help somebody do something: fix it, find it, heal it. They looked as if they’d risen up from the ground and were reaching out for one another with their stone arms, bewildered. St. Francis looks peaceful and ready to help in my neighbor’s yard here in Santa Fe. In Dublin there was a blue and white Virgin Mary leering from the top of my apartment complex. These symbolic hopes for intercession, for help point to entirely future-directed solutions and seem designed to take the suffering person entirely out of the moment.

When Ronan was diagnosed and I began to question these understandings of what healing means, I thought about the healing narratives in the Synoptic gospels, where Jesus heals the sick with a brush of his cloak, makes the unclean clean, casts out demons, sometimes a bunch of them at once, and makes the blind walk, the lame see, the barren fertile, etc. In any case, the body is a problem to be solved and Jesus can solve it. In light of what Ronan is teaching me I felt ready to have a solid crack at these narratives, and how they’ve perpetuated limited understandings of what healing might look like.

And then I read Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography by John Dominic Crossan and realized that I may have misunderstood these healing narratives, from my

earliest readings in Sunday school to the present. My companion at that long-ago concert had gotten it wrong as well. Here’s how:

In his quest to discover what we can truly know about the historical person of Jesus, Crossan draws not just on Biblical sources linked to the canonical

gospels, the “approved interpretation,” that we all know, in some form or other, but he also references sources that are independent of the gospels, in particular the Gospel of Thomas, a collection of the sayings of Jesus discovered in Upper Egypt in 1945 and that rocked Jesus scholars to the core. He also marshals his knowledge of medical anthropology, psychology, and ancient history of the Middle East.

Because the “body is society writ small,” bodies are able to “support or

challenge, affirm or negate a culture’s behavioral rules or a society’s

customary codes.” If you don’t comply with these codes of purity, you’re out. In other words, having a rash in the ancient world was, in fact, a tragedy because it was tantamount to absolute exclusion. The ill body was a symbolic

contamination, and the individual person who embodied this disorder needed to be excised as a way of protecting the whole.

This is important to Crossan’s argument that the historical Jesus didn’t actually perform miracles or heal anybody. Ever. The gospel writers needed to show the way in which Jesus extended Jewish notions of the Messiah, who, in keeping with Biblical tradition and stories, would be expected to perform miracles and feats of wonder. In the gospel stories then, Jesus performs miracles as a way of cementing his status, and he is often depicted as simply not being able to help it. (Don’t hate me because I heal you!) Someone brushes his cloak in a crowd and their tumor dissolves! Boom! Healed! The miracles are the byproduct of the Messiah’s arrival. Crossan, however, draws a sharp distinction between curing a disease and healing an illness, and this is the point I want to focus on. In Crossan’s words:

This is the central problem of what Jesus was doing in his healing miracles. Was he curing the disease through an intervention in the physical world, or was he healing the illness through an intervention in the social world? I presume that Jesus, who did not and could not cure that disease or any other one, healed the poor man’s illness by refusing to accept the disease’s ritual uncleanness and social ostracization. Jesus thereby forced others either to reject him from their community or to accept the leper within it as well. Since, however, we are ever dealing with the politic body, that act quite deliberately impugns the rights and prerogatives of society’s boundary keepers and controllers. By healing the illness without curing the disease, Jesus acted as an alternative boundary keeper in a way subversive to the established procedures of his society. Such an interpretation may seem to destroy the miracle. But miracles are not changes in the physical world as much as changes in the social world, and it is society that dictates, in any case, how we see, use, and explain that physical world. It would, of course, be nice to have certain miracles available to change the physical world totally uninhabitable; the question is whether we can make the social world humanly habitable.

Jesus didn’t heal. No miracles here. What he did was far more subversive and interesting, as it challenged the prevailing codes of social and moral behavior. According to Crossan’s understanding, Jesus rejected codified notions of who was in and who was out, and refused to let the traditional distinctions of clean versus unclean dictate his actions, his preaching, his promises of a better life, now, here, in the small villages clustered around the Sea of Galilee. This is why he was a revolutionary – because he sought to order society in a profoundly new way. To focus just on his actions relayed in the narratives (the healing act) and simplify their meaning (wholeness and health as understood from our modern, 21st century perspective) is to reduce the subversive powers of those very actions. Healing was not fixing the person’s body or ailment as much as it was a sense of acceptance of that person within the community. Jesus, a peasant Jewish Cynic who advocated free eating and healing, an open commensality that was absolutely new, and unequivocally subversive:

The Kingdom of God was not, for Jesus, a divine monopoly exclusively bound to his own person. It began on the level of the body and appeared as a shared community of healing and eating – that is to say, of spiritual and physical resources available to each and all without distinctions, discriminations, or hierarchies.

Healing, then, for Ronan, might be his full acceptance into community, into family, not the fixing of his physical body. Healing might mean no prayers for a miracle, but prayers for his peaceful, albeit short, life. Healing for him might mean people meeting him and experiencing his uniqueness, not thinking, “He’s blind, he’s paralyzed, he’s retarded.” As another Tay-Sachs mom pointed out to me, our minds are littered with these classifications that block us from seeing the beauty of individual souls housed in particular bodies, and it was this blockage that Jesus, according to Crossan, endeavored to clear. Reading the narratives in the light of Crossan’s scholarship gives me hope: it’s not Ronan’s body that is the ultimate problem, it’s the way others view what will be his brief trajectory in this world and the body that will take him on this journey. The miracle would be if everyone could accept him for who and what he is, including me.

After my Level 1 Reiki training there was a kind of initiation that I can only describe as a benediction, but instead of the pastor’s hands rising at the end of the service to send us out in the world, my eyes were closed and I felt the master’s hands sweeping and swooping through the air above my head, commanding me to use this energy for good alone. She asked me to heal others and myself (all Reiki practitioners can heal themselves). I would not be resurrected or reawakened into glossy, rosy-cheeked perfection, galloping through heaven on two flesh and blood legs. I was right to view that visualization of healing or wholeness as misguided. The potential of Ronan to heal and be healed has little to do with his body and more to do with how he is accepted in the larger world. That, perhaps, is the healing task, and if it happened universally, everywhere we went, it would indeed feel like a miracle.

Until I encountered Reiki and acupuncture and Crossan’s book, I had understood healing in a narrow, prescriptive way, as an endpoint predicated on the assumption that there is something deeply wrong with the person being healed. But the philosophies that undergird Reiki and acupuncture understand the body as a wise vessel having a unique and valuable experience, an experience that can be made more comfortable and wonderful through the treatments these systems of thought have generated and provide. My son’s body will not be healed. The Tay-Sachs disease, which seems accurately described as a demon, will not be “cast out.” His healing experiences don’t add up to “healing” the way I had previously understood it. If Jesus were alive and I jostled up to him in a crowd and touched his cloak, I would not suddenly grow a new leg, and Ronan would not start walking and talking. But as a result of the teachings of Jesus, as interpreted by Crossan in his meticulously researched, beautifully written book, people might have regarded Ronan and me differently, and with respect: the outcasts, the outsiders, brought into the communal fold. Having answered the question, “What’s wrong with you?” for as long as I can remember it, I can scarcely imagine such acceptance.

Today, for now, we take Ronan out to parties, to dinners, to restaurants. We let people hold him and play with him and feed him and meet him on his own terms. We try to make sure that his experiences inside his unique body are comfortable, and, whenever possible, full of wonder. We love him now, in the moment, and every day and we will do this until his last day. That full, uncompromising love, powerful and sometimes painful, is perhaps the only miracle worth believing in.